Preparation, Interpretation, Improvisation

I.

I want to take another run at what I was trying to figure out in "The Mysterious Appeal of Emergent Narrative." I'm going to use Matthew A Olson's "July 2025’s RPG Blog Carnival: Improv, Roleplay, and Warmups" as a pretext to do it, because I've realized that improvisation might be a useful way in. He's asking about "how we approach in-the-moment character development, immersion, role play, active play, and improvisation" (emphasis his). Unfortunately, while I do want to talk about improvisation and roleplay, none of the specific prompts Olson lists really provide that way in. Based on the way he describes improvisation early in the post, I suspect the prompts don't work for me because we might approach improvisation a bit differently. For example, he repeats phrases like, "quick and nimble problem-solving," and asks a few times about low-prep GMing. But I find I improvise best when I've first done a lot of preparation.

(My apologies in advance if I belabour anything obvious or well-trod; mostly this is because none of what I'm about to discuss was obvious to me, but it's also because I want to make each step as clear as I can before moving to the next.)

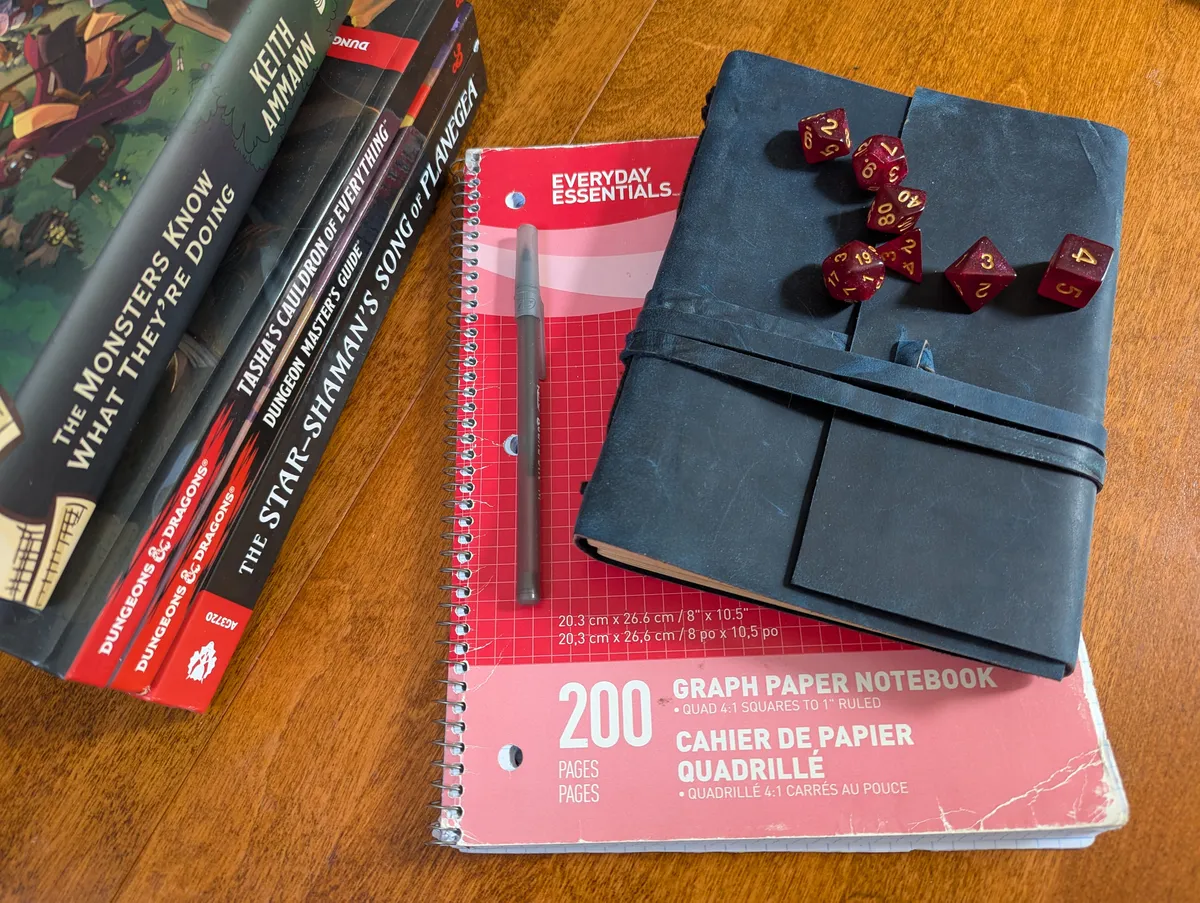

Source: Christian Hendriks, July 2025

Source: Christian Hendriks, July 2025

Nearly every decision I have regretted as a GM has been a case either where I was under-prepared or where I forgot in the moment what I had prepared in advance. The decisions I am happiest with vary much more considerably: those where I prepared carefully and delivered exactly what I had planned; those where I realized in the moment that what I had prepared didn't work, so I replaced it with something else on the fly; and those where the players did something unexpected and I adjusted a carefully-planned encounter in response. The reason I'm happy with these decisions is mostly because the player feedback was good, so my satisfaction with these moments isn't just a question of my own disposition. These moments really were, I think, the ones that worked best. What the successes had in common, and what sets them apart from the failures, is that I fully understood the situation in those cases. When I fully understand a situation and how it relates to the rest of the story, I can make better decisions about what to keep, what to replace, and how to extemporize. I can only attain that understanding through lots of preparation.1

II.

Of course, other people improvise quite confidently without this level of preparation. Part of it has to do with different aesthetic or ludic standards: the kinds of games I like are ones with intricate and internally-consistent stories, which are easier to run with preparation. The point for now is just that a table that cares about different things (or a table that cares about this consistency but can reliably achieve it without preparation) is likely to get more out of a low- or no-preparation style than I will. However, there is something that is common to all good improvisation that is just more obvious when it involves preparation: all good improvisation starts with interpretation.

I think if you ask a person to tell you, off the cuff, what improvisation means, they'd most likely say it means coming up with something on the spot. But that's not really how we use the word. At least, everything we call improvisation does something else, too: it builds on what came before. Improv sketches are built on prompts. A stand-up comedian's improvised jokes are almost always crowd work, where they respond to what the audience says. At the gaming table, we respond to the dice, to the rules, and to each others' improvisations. And if improvisation is a creative response, then first of all the improviser must interpret what it is they are responding to. (Think of how boring it is to play with someone, whether a player or a GM, whose storytelling choices always only develop what they already decided about their character, and never meaningfully engage with the setting or the other PCs.)

There's a cycle, therefore, in roleplay:

contribution of some material → interpretation of that contribution → contribution of new material → interpretation of that contribution → etc

Here's an example, replacing each step with something more specific:

GM describes a scene [contribution] → players listen and form opinions and questions [interpretation] → one player asks a question and rolls 18 on a Perception check [contribution] → GM considers what an 18 + relevant modifiers will get the PC [interpretation] → GM mentions the anachronistic sewer grate is askew and the kumquat vendor's fruits are arranged on blocks to make it look like she has more wares than she does [contribution]

I skipped some steps, of course: the Perception check "contribution" in that example is at least a few cycles by itself. The point of the example is just to show the different kinds of contributions that require interpretations: roleplay and rollplay are both contributions. But it's actually even more complicated than that, though, isn't it? Because it really looks like this:

contribution of some material → interpretation of that contribution in light of all previous contributions → contribution of new material in response to all previous interpretations → interpretation of that contribution in light of all previous contributions → etc

And probably it's still more complicated than that, but that's plenty sophisticated for now.

Quick, on-the-fly improv follows this pattern, but so too does more deliberative GMing. Your intuitions may differ about whether any advance preparation can itself be improvisation (you probably wouldn't have much success using the word that way), but one example of a contribution → interpretation → contribution cycle appears in Nick Hendriks's "I pre-roll my random encounters" at his eponymous blog:

None of this is stuff I couldn't potentially come up with on the fly, but pre-rolling it gives me more chances to really turn it into something special. I can review a few possibilities and decide which one I like. I can go on to prepare names and personalities for NPCs, and to workshop other details: sights, sounds, smells, etc. The charlatan has a unique perfume on his powdered wig. The bandit's leather boots are creaking with every shift of their weight, not yet broken in. The angry boar looks to have a mix of wild hog and domestic pig markings, maybe indicating the presence of a local settlement. That kind of stuff.

Another GM might roll on an encounter table and interpret the results in situ, while Nick does it beforehand; we might only call the first improvisation, but it's otherwise the same process. So this cycle does not need to be "quick" or "nimble" by definition. It does need to be nimble and reasonably quick when the players and GM are responding to each other during a session, of course! However, I think part of the reason I'm struggling with Olson's prompts is that I don't really value this quickness for its own sake, even if I acknowledge that it takes and therefore demonstrates more skill to do it quickly. What's satisfying to me is the contribution → interpretation → contribution cycle, not the speed at which it is done. A rapid back-and-forth has its own appeal, of course; I'm just more interested in other things.

III.

I promise this was not meant to be a nit-picking post, even if that's how it's shaping up, but as an illustration I do want to bring up something I think Ben Robbins missed in his otherwise quite observant post "We Say 'I Think…'." Robbins noticed a verbal pattern at his table:

[...] when we make contributions during a game, very often we’ll start by saying “I think…”

I think the city towers are incredibly tall, but also kind of precarious

I think when she comes into the room she has this look on her face like ‘what’s all this about??’

I think the storm is dying down now…

If you listened to a recording of one of our games, you would hear it all the time. We use it so often that, to us, the “I think” is nearly invisible, like clearing your throat or saying “ummm”. When I started being really conscious of it and listened for it, it amazed me how often we said it.

He explains what he thinks is happening here:

We do it even when one person definitely has the sole responsibility of saying what’s true right then. Saying “I think…” is not an actual invitation to negotiate content. Instead it is good manners and telegraphs a very essential attitude.

It signals that you recognize that the whole game is a mutual process: even when the rules say one person has total authority, we know the process only works if everyone else at the table embraces what we make. Ultimately, everything is a suggestion, because if the rest of us aren’t into the idea, the game fails, or at least this idea doesn’t have a lot of legs. Because these games are entirely about finding agreement.

I can't say he's right or wrong about his use of "I think," or his players', or its use in story games or the Pacific Northwest, but I really don't think any of this is why I use "I think." Because I do use it, and I sometimes notice others using it, too. I have also made a note of it. When I say, "I think," though, it is because I am still interpreting as I improvise. I say, "I think she lowers her spear," and what I mean is, "The way I understand this character and this situation, I think she would lower her spear. I'm not entirely sure about that, but that's what I'm going to go with." If I am sure, I just say, "She lowers her spear." Or if I don't think I know nearly enough about her to say what she would do, and I just have to decide on something, I usually say, "I'm going to say she lowers her spear." "I think" comes in the moment when the fact I'm interpreting is not invisible to me.2

That highlights something important: the interpretation stage is not passive, not at all. It also requires creativity, and it requires more creativity when the parts of the story do not explicitly fit together, because then the interpreter has to make them fit. The obvious example is when the PCs are investigating a well-made mystery; even if they are not making many contributions to the narrative in terms of impact on the setting or plot, engaged players are interpreting in overdrive. Interpretation is also active when players are making tactical decisions with incomplete information. It's less the case that interpretation is creative when the players have very little information at all. We have to have something to interpret, and the more scenes and characters and objects and facts there are, the more gaps there can be between the scenes, characters, objects, and facts.

IV.

All of this comes partway to explaining why I improvise with more confidence, and with apparently better results, the more preparation I've done: there are more contributions in light of which to interpret new contributions, more parts to which I can connect the pieces my players add, and more information I can use to say what an NPC would do.3 This also brings me, at last, to narrative kitbashing.

Although my previous post (the one I mentioned in the first sentence of this post and not once since) had "narrative emergence" in the title, I was really trying to figure out what the thing below narrative emergence is. I was trying to work out the reason I like it so much, which I suspect is what narrative emergence has in common with early modern epics. The name I settled on for that underlying thing is "narrative kitbashing." But I did not properly explain it, mostly because I did not have a clear idea of it at the time myself. Having thought about it in the months since that post, I think what I mean by narrative kitbashing is the use of the narrative objects you happen to have in front of you to make something that suits your narrative vision. Those objects can be the indispensable tropes of the early modern epic tradition, those digressions and descents to the underworld and divine interventions and catalogues and descriptions of the dawn that a sixteenth- or seventeenth-century poet needed to find some use for if he wanted what he wrote to be an early modern epic at all. These objects could instead be the results of the dice or your collaborators' contributions – anything extrinsic to your vision. By "vision," here, I don't mean to imply you have some specific plot you want to enact; I mean the combination of your assumption about the kind of game you're playing, your aesthetic and ludic standards for those kinds of games, and your beliefs about how the world works, at least as they're relevant to the story you're building together.

Emergent narrative relies on narrative kitbashing: the elements we're building our improvisation on were not made or chosen to have any kind of relation with one another, but we interpret them as though they are related, and make sense of them that way. According to the encounter table and the dice, there are 1d6+2 goblins in this room, which is leaking in the southwest corner: from these elements, the GM figures out not just what the goblins are doing in the room (maybe they are repairing the leak), but what that says about the goblins who live in the dungeon. And the players do that, too: by interpreting noise, the players make a signal. And then, the interpretation begun, we start to improvise, each of us providing more for the others to interpret, and on it goes. But the thing I want, anyway, doesn't have to be an emergent narrative; the thing I'm looking for is the thing underneath, what I'm calling narrative kitbashing.

I think.

I haven't read much of the academic literature on TTRPGs or on improv, but I have read some of it, and what little I've read is enough for me to know that someone, surely, must have made this connection before me – some academic somewhere has stressed the importance of interpretation in the act of improvisation, in general and in RPGs specifically. If you are aware of that literature, please feel free to let me know in a comment – because I have comments now! I think they are still a little janky, in that they are centre-aligned and I do not know how to fix that. Maybe I will have figured it out by the time you read this. Maybe I won't have gotten it figured out and will have deleted the commenting function out of frustration by the time you read this. At present I cannot say.

There are other reasons I need to adopt a preparation-heavy style, at least in my main campaign, which has to do with my players' needs: theatre of the mind doesn't work well for at least one of my players, so I need to use battle maps, and I haven't the artistic skill to produce adequate battle maps quickly on the spot. (Believe me, I tried.) I therefore need to find battle maps in advance, which in turn means I need to prepare possible encounters in advance. Now, I have run shorter Fate Core mini-campaigns with a much lower-prep style as a kind of experiment, and that went well enough. For the most part, though, I could not avoid substantial prep even if I wanted to.↩

I came upon "We Say 'I Think'" while I failed to find a different post on ars ludi. I swear Robbins has a post somewhere in which he describes a kind of moment in a story game, where a player hears another player's contribution and says, "Oh, of course! That must be why the elves stopped building along the river," or something like that. Obviously that isn't why the elves stopped building along the river, not really; the elves stopped building along the river because one of the players said so, or at least implied it. But our brains like finding patterns and causes and intentions, so it feels like the detail one player made up is the reason for a detail that a different player made up previously. And because it's fiction, we get to say that it is! These are moments where you don't say, "I think she lowers her spear"; you say, "Oh, of course she lowers her spear! Right at you!" I can't find this post, however, and now I am starting to doubt it was on ars ludi at all, so I have to relegate this uncitable discussion to a mere footnote.↩

This says something, I guess, about what kinds of player or GM are more attracted to what kinds of play: you have to be able to remember most of the previous contributions, and keep them all in your head together, to benefit from this preparation. I don't think this can be reduced entirely to something like autism vs. ADHD, because I know there are GMs with ADHD who tend more toward prep and autistic GMs who eschew it, but I do think it's fair to sometimes say, "I don't have a brain that can do all that," or, "I have a brain that needs all that." Sometimes.↩