How I Plan Horror Games

Horror games are not what I run most often, but from time to time I run Chronicles of Darkness games, or Fate Core adaptations of Chronicles of Darkness setting lore. In fact, it's become a bit of an annual tradition among a few close friends and I to play a horror game around Hallowe'en. October is the month for discussing all things horror, so I thought I'd share two techniques I have developed for my own Chronicles of Darkness games, especially as I haven't seen anyone else discuss them yet.

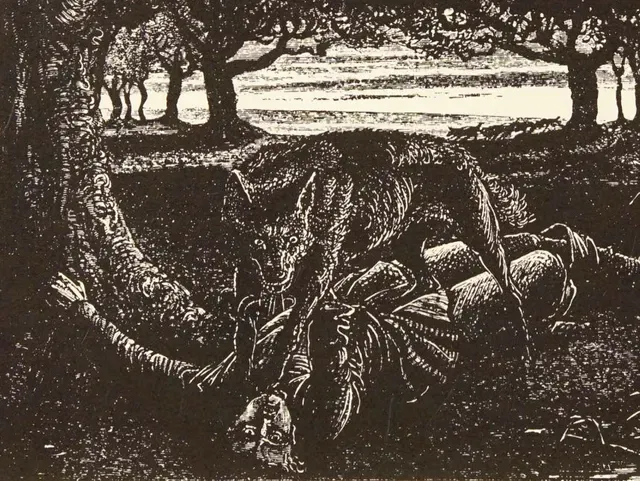

Source: Sabine Baring-Gould's The Book of Were-Wolves: Being an Account of a Terrible Superstition (1865), via the Public Domain Review.

Fine-Tuning Fear

In my now-traditional Hallowe'en games, I have a bit of a challenge. They started because one of my dearest friends, a fan of horror movies, asked me to run a horror game for her and two mutual friends. Considering I had been reading through most of the Chronicles of Darkness and related sourcebooks available at that time,1 I was very interested: it's always nice when your friends ask you to run the game you'd been planning to cajole them into playing with you. The trouble, though, is that one of those mutual friends is easily scared by horror movies, and not a fan of horror in general. For the sake of this explanation, I'll anonymize my friends as so:

- R asked for the horror games, and is a particular fan of horror movies;

- J watches horror movies (I think especially ones with ghosts), but is not as big of a horror fan as R is; she also has "spiders" listed under her Lines;

- L is more easily scared by horror movies and does not enjoy that experience, though she has watched a few for various reasons.

The recurring challenge, then, is to make a game that satisfies R without scaring L too much, despite the fact that L is easier to scare than R. There's no formula for success here, but I have found a few things that work.

First, I carefully considered what R finds satisfying in the horror genre. After speaking with her about it a bit and thinking over previous conversations with her, I focused on the fact that she doesn't like horror that holds back what the monster is; she wants to see the creature, in large part because she likes well-designed creatures. So I knew that, to satisfy R, I should let them find out by the end what they were dealing with (or had been dealing with, if the reveal follows the final confrontation), and I should have at least one creative supernatural horror. For instance, my games have included the following:

- the Man in the Wall,2 a phantasmal masked knife-wielding killer created by a magic artifact that manifests the deepest fears of the people nearby; he has only an incomplete face under his mask, and apparently lives in the walls of an apartment building, despite those walls being far too thin for an adult to fit inside them; he enters and exits the walls through sliding panels that don't otherwise seem to exist;

- a spirit of paranoia that possessed Amber, L's character, shaped like a centipede; centipedes are great in horror because they both slither and skitter; when the PCs exorcised it from Amber, I could also describe it as slithering out of her mouth, which I think is a nicely revolting image, if a little on the cliché side;

- a little roadkill spirit that looked like three squirrels mashed together by car tires, trailing gore through the wet autumn leaves as it crawled with limbs pointed in various directions;

- the coughing ghost of William J. Candler, a necromancer who died in a warehouse fire in the 1930s; his eyes are burnt out of his skull, with dim embers glowing in blackened sockets; on cords and chains around his neck he wears scores of coins, cloths scraps, ceramic shards, and other tokens, all with eyes painted or etched on them in white, including a pair of spectacles with an eye scratched into each of the lenses, which he puts on when he appears; the sleeves of his oversized pea coat smoulder and soot comes out of his mouth when he coughs;

- the friendly ghost of Hazel, a young oracular hippy woman, who was wearing sheer tights and a long-sleeved floral-print sack dress when she died of an embolism; her ghost had long, braided hair and held her head in her hands – literally, as her head was disconnected from her shoulders; flowers and trailing plants spilled from the place where her neck should be

Learning what my primary horror fan wants out of horror besides fear helps me compensate for the lower-grade scariness I would have to use.3

Another thing that many people, and all of my players, enjoy about horror are evocative details and atmosphere. Gothic horror uses evocative details that can make the game more engaging, and still feel like horror, without having to actually be scary. There can be a beauty to the sad and the sordid, if done well. In my most recent set of games, R and L specifically complimented the Mementos I included, which I either adapted from ones in official Geist the Sin-Eater material or invented whole-cloth:

- the Cold Harbor diary, unmodified;

- a modification of the digger's mojo bag; it functions the same, but instead of being a bag on a cord, it's three locks of hair braided together dangling on a ribbon, made by Victorian necromancers: two sisters and the woman they were rumoured to have taken as their lover;

- a modification of the empty dance card; like the original it's a dance card with the lines left blank, but it functions differently: if the person holding it performs one of the dances on the card, the names of the twelve nearest people, living or dead, appear written in cursive on the card's blank lines;

- a silver statuette of an allegorical figure of victory that shudders rhythmically when held in the presence of a ghost; a woman used it to kill her lover's wife, and then her lover used it to kill her when he walked in on what she'd done; its thuds are reminiscent of striking a human head with it;

- a deck of playing cards that will always give a dying player a good hand;

- a deathmask in the form of a Victorian fencing mask; appears splattered with fresh blood only when worn; allows the wearer to see ghosts (except those of relatives).

I hoped that the dance card would appeal to J, who loves ballroom dance. As it happens, the players assumed you needed two people to do the dances, because all the dances are partnered; this means that they always used the empty dance card in pairs, which I thought resulted in a series of very cute moments. I also suspected, rightly as it turns out, that R would get a kick out of the implied lesbian non-monogamy in the braided locks of hair. Specifically, she said, "Oh, she hooked up with hot twins. Good for her." I pointed out that I never specified the sisters were hot or twins, but that's how R took it. Her character Pansy then insisted on braiding the PCs' hair together while the other two did research, saying, "There's three of us, and we have hair."

All this is well and good, and helps make the games satisfying if I should fail to make it scary, but also I do at least try to make it scary for R without making it too scary for L. The way I most recently attempted this was to use visuals that meet three criteria:

- they disturb R;

- they do not disturb L or J; and

- no one listed them among their Lines and Veils.

Specifically, R is bothered by eyespots, but did not list them among her Lines and Veils (probably because it's seeing them, not hearing about them, that bothers her) so I loaded William J. Candler's ghost up with artificial eyes. This description still stood a chance of making him a little bit scarier for her without making him meaningfully scarier for J or L and without making R uncomfortable in a way she would not want to be uncomfortable. I don't know exactly how well it worked, but as it happens R complimented my design of Candler as a horror movie creature and L at least confirmed that Candler was exactly as scary as she could handle: if he were any creepier, it would have been too much.

Unfortunately, it isn't easy to repeat this trick with the same players: the other things that I know bother R are ones she listed in her Lines and Veils, and I can't give every monster they face loads of eyespots. In the meantime, while I consider what else could make a good monster for R, I'm thinking about what interests J or L, so that I can fine-tune these Hallowe'en games by including or excluding elements that my players will respond to differently. In other words, knowing your players and paying attention to what they want from a game can help make a session that is satisfactory to everyone. Going forward, I should likely attend more closely to what J and L would like out of these sessions to make sure they can engage fully.

Connections to Real-Life Horror

William J. Candler's false eyes aren't there just to creep out R, however; the reason they're all white is that he's a racist and eugenicist. He literally sees through eyes of whiteness.

I've developed a habit, or perhaps technique, of grounding the supernatural horror of these games in anxiety-inducing situations in real-life. This started in the first horror games I ran for J, L, and R, a short campaign in which I channeled my frustration with a certain property management company: in particular, a REIT ubiquitous in northern Canada managed a building I lived in that was repeatedly infested with bedbugs, costing me over a thousand dollars in lost furniture and in pet boarding fees. Adding insult to injury, when I went in once to report that the bedbugs had returned, they tried to blame the infestation on me and my rabbits; while bedbugs are attracted to rabbits, I do not understand how the insects could have crawled from a neighbouring building into ours during the -20 to -40 degree temperatures at the time. (Besides, the REIT owned the neighbouring buildings, too.) Remembering this, I was reminded of Stephen King's Danse Macabre (1981), in which he discussed The Amityville Horror (1979) as a film charged by the fear of poverty: any person who's familiar with financial hardship, King says, knows the fear of sticky windows that can crash down on your fingers and knows how terrifying it is to lose your wallet when it contains all of the money you have. So for my first horror game, I designed a scenario where one character's apartment (Amber's, as it happens) had a horrible mould outbreak; when she and her friends reported it to the building's property managers, they not only dragged their feet on dealing with it, but they also tried to blame the mould on her. Of course, because it was a supernatural horror game, the mould had a supernatural cause, and by the time the game was finished they had fought the Man in the Walls and had confronted some of their own most basic terrors. The negligent REIT was not the primary antagonist, but it contributed to the game's anxiety and its oppressive atmosphere.

Pleased with how that game went, I've approached most of my horror games by building around a kernel of real-life evil or looking for points of connection between the Chronicles of Darkness and current events. Here's a list of horror games I've run with this in mind:

- For a different pair of players (including my brother Nick Hendriks) I ran a mini-campaign I called Hunting the Blue Beast, in which the PCs faced a monster that lived off victims' fear and therefore masqueraded as a cop (for which I must surely have had the 2001 Angel episode "The Thin Dead Line" in the back of my mind);

- In the next Hallowe'en game I ran for J, L, and R, which was supposed to be a single session but actually took two, the villain was a shadow occultist who hunted at gem shows and other New Age events, turning people into lures for spirit possession by giving them fake "exotic" charms, exploiting the gullibility and comfort with cultural appropriation that makes some elements of the New Age movement vulnerable to grifters;

- In the last Hallowe'en game for J, L, and R, which again was supposed to be a single session but took three, a Protestant evangelical politician positioning himself as a heritage candidate started dabbling in necromancy, trying to literally manipulate the past in order to advance his own political career and ideological agenda – but he accidentally summoned the ghost of William J. Candler, described above, who began manipulating the politician in turn.

The connections to real-life problems should be fairly obvious: police violence and terror; the strange hybrid of skepticism and gullibility that permeates both the New Age movement and MAGA conservatism; the way the heritage-style conservatism of people like Stephen Harper morphed into (or was usurped by) the outright historical revisionism and eugenicism of MAGA-style conservatives, and how trying to use the past for your own agenda seems to summon the worst politics of that past. The last one also reflects a bit on the way evangelical Christians sometimes use spiritual means for careerist ends. Some of these are metaphors: the Begotten cop is a metaphor for police violence, and the necromancy is a metaphor for historical revisionism. In other cases, the real-world problem creates space for, or worsens, the supernatural problem: the property managers' negligence means the PCs have to deal with the magical artifact on their own; the reasons the New Age movement is vulnerable to grifters are also reasons it is vulnerable to predatory occultists.

I use these metaphors and connections for two main reasons: first, it helps me choose between the vast array of possibilities that Chronicles of Darkness presents, narrowing my focus; second, it makes the games more interesting to me, providing both a challenge and an outlet as I figure out what modern anxiety I can explore this Hallowe'en. I think it has an additional benefit, however: it charges the game with a real anxiety that no amount of eyespots would otherwise have. For instance, the players in "Hunting the Blue Beast" told me it was nerve-wracking whenever I narrated police sirens passing the motel their PCs were hiding out in, even though these sirens never amounted to anything.

However, I also try not to overdo it; the supernatural threat should be sufficiently distant from the real-world problem that the first only suggests the second, without the second overwhelming the first. If it's a metaphor, there should be just enough distance between tenor and vehicle that the PCs aren't tackling the tenor as well as the vehicle. In other words, the PCs aren't really fighting police brutality: they are fighting a monster disguised as police. The same is true when the real-world problem creates space for the supernatural problem: the PCs are investigating an apparent haunting, not fighting a property management company. If the game gets too close to things that genuinely upset the players, that can take the fun out of the game. But it can also take the fear out of the game: when horror is political like this, there's always a risk that a sense of justice and self-righteousness can override the discomfort.4 It's a fine line to walk and I'm not sure I always manage it, but I think so far it has worked for me more often than it hasn't.

Parting Thoughts

I'm reluctant to frame gaming lessons as pieces of advice: I often think it's better if I tell you what I've done and why I think it did (or didn't) work, and leave you to draw your own conclusions about how it applies to your table. However, in the spirit of recent posts by Nate Whittington and my brother Nick, I'll try to distill the above post into a few actionable insights:

- Horror games are a great opportunity to use your knowledge of your close friends against them (so long as you don't cross their Lines and Veils).

- Centipedes are underused critters in horror games, who both skitter and slither and can therefore partially replace spiders in games with arachnophobic players and snakes in games with ophidiophobic ones.

- Creative and evocative images can make horror games still feel like horror games even if they aren't actually scary.

- Creating supernatural threats out of real-world evils can give horror games an extra verve, so long as you are careful and thoughtful about it.

I find the different editions of World of Darkness needlessly confusing and Byzantine, so I will only list examples rather than try to define the boundaries: I'm talking about Chronicles of Darkness; Demon the Descent; the 1st and 2nd editions of gamelines like Vampire the Requiem, Mage the Awakened, Geist the Sin Eaters, Changeling the Lost, etc.; and Beast the Primordial and Deviant the Renegade. I have almost no interest in parallel World of Darkness titles like Vampire the Masquerade, Mage the Ascended, and so on.↩

I took the name and therefore idea for this monster from Girard's discussion of A Midsummer Night's Dream in his book A Theater of Envy: William Shakespeare, though the monster otherwise has nothing to do with either the book or the play.↩

I also watched one of R's favourite horror films, Neil Marshall's The Descent (2005), but I realized that what she likes about it wouldn't work for the game we were playing: she has said the reason The Descent appeals to her is its depiction of people who know each other's worst faults all trapped together. I prefer to run collaborative tables, and this table in particular is a peaceable one, so I knew immediately that the dynamic in The Descent wasn't going to work.↩

I'm not sure where the balance tips from discomfort to righteousness, but if you want to think about this further, I can point you in two directions. First, I think Mariana Colín poses the problem compellingly in her 2020 video, "The Real Reason The Thing (1982) is Better than The Thing (2011)," at around the 5:45 mark (content warning: lots of body horror visuals). I worry, though, that she accidentally overstates the case a little bit: from her other videos, it's clear she knows horror with metaphorical and political content can work sometimes. Second, I wonder if there are answers in Richard Beck's writing on Terror Management Theory and bad Christian art (part 1, an interlude, part 2, and part 3); he finds that looking at ideologically-confirming art helps people manage their fear of death. Although the art Beck has in mind is saccharine, I wonder if politically-charged art can have the same effect if it confirms the viewer's values in the same way. After all, it's the confirmation of their values that helps insulate the viewer from their existential terror. (This will make sense if you understand Terror Management Theory, which is just a little too complicated to explain here.) So maybe when the political relevance of a horror game monster is too on the nose, the player's value system is confirmed and their fear is lessened? If so, that might be something to keep in mind if you want to reduce a player's fear.↩